The Evolution of Madness and its Treatment

Three Key Concepts Previewed in Michel Foucault’s First Book

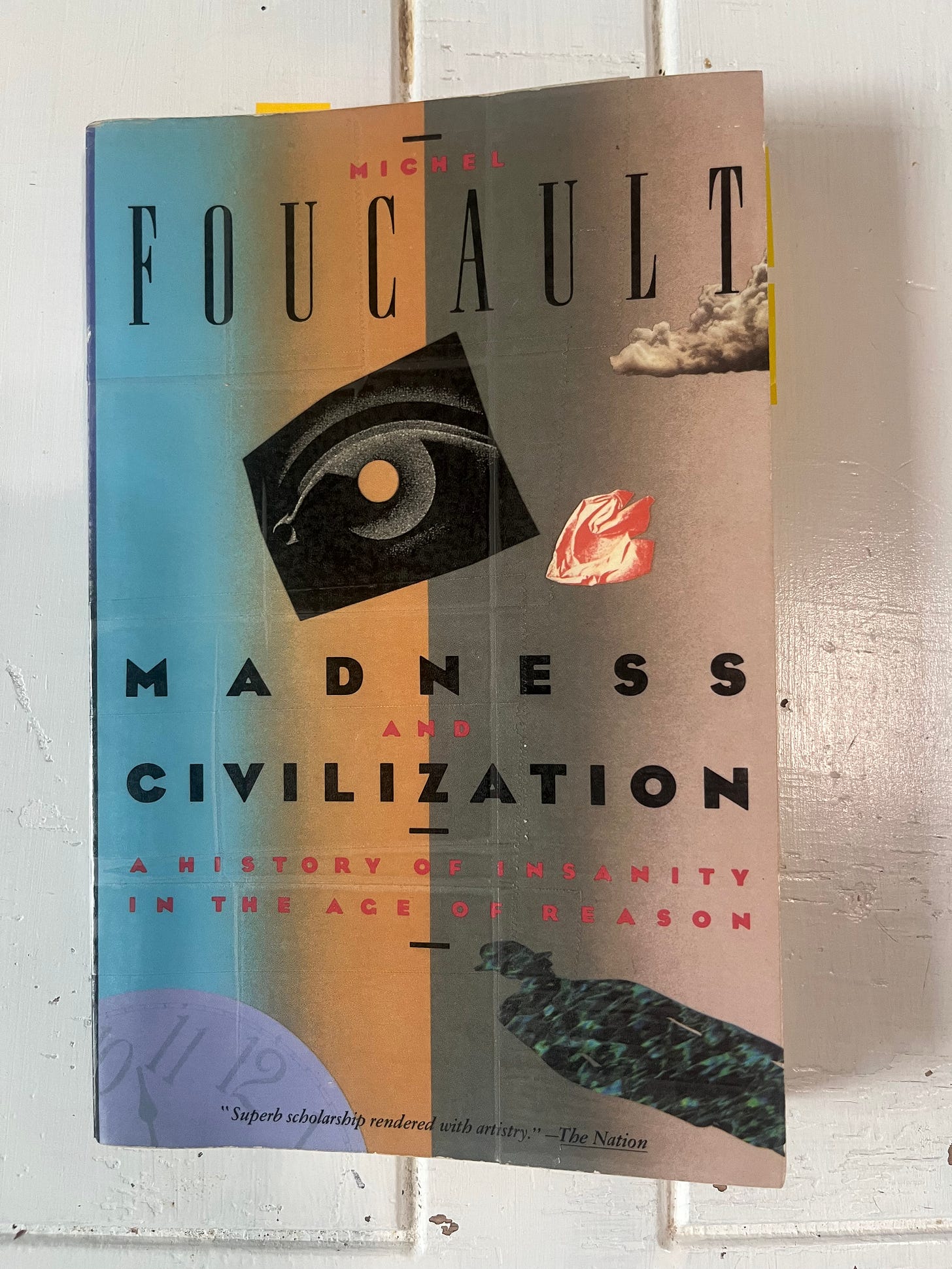

The French philosopher Michel Foucault is one of the most cited thinkers in the humanities and social sciences, tallying nearly 400,000 citations just since the year 2019 according to the Google Scholar index. Madness and Civilization, published in French in 1961, constitutes Foucault’s first major work. However, it is not highly cited relative to his other works. I review it here as a way to investigate how this early text might help us better understand Foucault’s later, more influential ideas.

I first heard about Foucault while competing in debate. He was the “it” philosopher around 2006 in the debate community. His ideas were regularly deployed to substantiate what were called kritik arguments1 (or ways to change the subject from the debate resolution by disputing the validity of the topic’s framing or the concept of debate itself). Although I presented these arguments based on his works, I had not yet read Foucault.

When strolling through a bookstore as a soon-to-be college student, I noticed this unassuming paperback and I had to have it. I had no sense of where it fit into Foucault’s corpus (I don’t think I knew the word “corpus”), but it promised to explain the history of madness and I, too, wanted to be—or at least sound—smart like those debaters who asserted Foucault kritiks with greater confidence than I could muster. I treated it as an advanced reading assignment for college and eagerly began to read it.

Unfortunately, I struggled immensely to understand what Foucault was trying to say! The historical references were unfamiliar, the plethora of French words and literary allusions too. There were no explanatory footnotes. I was quite simply clueless— not that eighteen- year-old me would have admitted as much. I later grappled with many of Foucault’s ideas in graduate school. With the help of patient seminar leaders, and even more patient peers, I began to understand how Foucault saw the world.

To the best of my recollection, I was never assigned, nor did I bother to consult, this book during those seminars. It simply gathered dust on my bookshelf, next to the other Foucault volumes that did get used. Upon return to Madness and Civilization almost two decades later, I was pleased to see how Foucault’s ideas began to come into focus— and glad I held onto this book.

What follows is a brief synopsis of the book and then a description of what I take to be early iterations of three important Foucaultian ideas: the juridical, biopolitics, and truth. I will conclude by offering some big picture take-aways about what the book, its author, and what they reveal about contemporary approaches to thinking and talking about mental illness.

1. Synopsis

The book describes the history of madness beginning around the year 1500 C.E. Foucault is most interested in investigating developments during what he refers to as the “classical period.” When Foucault uses this phrase, he speaks not of Greco-Roman antiquity, but of seventeenth and eighteenth century Europe (ca. 1600 to 1800 C.E.).

Over that time, the image of what it meant to be “mad” transformed substantially, from the ship of fools, as depicted in Hieronymus Bosch’s painting (ca. 1490), to that of a clinical environment we might picture today. In short, we went from thinking about those with mental illness as simply different and mostly harmless to thinking about the insane as those needing fixing, so they could conform to social norms.

Whereas the wise fool character in Medieval and Renaissance literature was thought to possess a type of uncanny wisdom, this began to change when a new conception of madness emerged in Europe. As Foucault put it, madness was “moored now, made fast among things and men. Retained and maintained. No longer a ship but a hospital.”2

A Ship of Fools, A Painting by Hieronymus Bosch ca. 1490 — Public Domain

The opening of the Hôpital Général in 1656 in Paris marked the beginning of a period called the Great Confinement. People who were considered insane were rounded up and housed alongside criminals, the infirm, and those who “refused” to work. Within a few years of its opening, this institution held over 6000 people, about 1% of the local population at the time.3 Confinement was simultaneously a response to an economic problem and a social one. In addition to confining those unable to keep a job and forcing them to work, it became “a moral institution responsible for punishing, for correcting” violations of social norms of the upper classes by stigmatizing them as not normal.

In the middle portions of the book, Foucault tries to categorize different types of madness. Those interested in the history of psychiatry may find these chapters valuable, but they largely rehash old ideas that contemporary psychiatrists would not take seriously. Some of the claims are blatantly misogynist. Still, this context is arguably necessary to inform what follows.

From there, Foucault begins to explain how we began to think of madness as a psychological ailment rather than a physical one. At first glance, it may appear that the mentally ill (a phrase Foucault puts within scare quotes) are treated better as we move closer to modernity. However, this comes with a twist: medicalization is simply a different— and perhaps more effective—way to exert power to enforce conformity.

At the conclusion of the book he begins to sketch out what the new norm surrounding insanity had become. The penultimate chapter, titled “The Birth of the Asylum,” remains the most valuable to read in my view, although it is difficult to understand without an understanding of how Foucault gets there.

2. Juridical Power

The pre-classical era (before about 1600) was still the age of sovereign or juridical power. Foucault uses this term to refer to the power of the state over life and death of its subjects, what the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes called the Leviathan.

Foucault believed that sovereign power was dying, but not yet dead. The classical period served as a transition between an era in which the state controlled the right to punish, compel, or even kill in the name of preserving the society (sovereign power), to one in which it uses more subtle methods to control populations, & where subjects voluntarily treat or punish themselves (biopower).

During the great confinement, forced labor served a slightly different function than than traditional juridical power, but retained traces of it. The confinement of criminals, the mad, the infirm, and other undesirables served a dual function. On the one hand, it punished by asserting direct control over the bodies of the confined population. On the other hand, it affirmed a set of societal values, not through persuasion, but through psychological coercion.

3. The Emergence of Biopolitics

When the asylum replaced earlier practices of confinement, we see the emergence of biopolitics as the norm enforcer for psychological health. The term biopolitics refers to the use of government power to control how people live. No longer a labor camp, the asylum became a sort of “retreat.” Prison officials were replaced by doctors. The new asylum regime did away with overt coercion and punishment. Instead, patients were expected to make themselves well. The madman, Foucault says, “is no longer guilty, [rather he] must feel morally responsible for everything within him that may disturb morality and society, and must hold no one but himself responsible for the punishment he receives.”4

The drive to medicalize psychological ailments coincided with public fear that madmen might “infect” the population at large. Not coincidentally, most asylums existed where previously there had been lazar houses (places to confine those with leprosy). This association extended to the discourses surrounding this apparently kinder, gentler approach to mental illness. People were to fear those suffering from madness. It was

A fear formulated in medical terms but animated, basically by a moral myth. People were in dread of a mysterious disease that spread, it was said, from the houses of confinement and would soon threaten the cities.5

Put in contemporary terms, madness became distinctly a public health concern. As a result, deviations from “normal” were stigmatized and treated.

Michel Focault in Brazil ca. 1974 — Public Domain

4. Truth & Conformity

Throughout the book, Foucault traces the evolution of what he would later call a regime of truth with respect to madness and sanity. This idea of truth is not objective or universal.6 Rather, truths for Foucault are the realities we accept as being true—a strong form of social norms. I like to think of this concept as those things to which we are expected to conform, and will face social sanction if we do not. Unlike objective Truth, regimes of truth are not immutable. They will vary across time, space, and culture.

Foucault wrote that “each society has its régime of truth, its ‘general politics’ of truth: that is, the types of discourses which it accepts and makes function as true.”7 Here two illustrative examples. In colonial Massachusetts, belief that the community was filled with witches became a regime of truth; people operated as though it were true despite falsifying evidence. The Islamic State (ISIS) terrorist movement crafted a distinct set of beliefs about the role of women, jihad, and martyrdom that they made true through discursive practice, as well as the threat of force. Most would reject these belief systems as mistaken, if not malicious, but they functioned as true in those societies. That’s all Foucault meant by “truth.”

Collectively, Foucault’s first book enacts this style of thinking to better understand what it means to be mad or sane within Europe from roughly 1500 to 1900, but without doing the abstract conceptual work he would complete in subsequent works, such as The Order of Things and Archeology of Knowledge.

5. Take-away Lessons

As I see it, Madness and Civilization describes the exercise of three forms of power and considers how they are related. Those forms of power are exerted on the body, the psyche, and the population at large. On the body, they demand labor without consent of the laborer and retain the right to kill. On the psyche, they function by enforcing categories (e.g., sick/well, mad/normal, smart/dumb) to promote conformity. At the population level, they exercise power to make live or let die— as opposed to kill or let live, as it was during eras of juridical power.

It is also one of the first works to seriously consider how medicalizing mental conditions may bring its own consequences. Although seemingly more humane at the individual level, at the population level and within the psyche, this approach promotes conformity and reduces freedom. Although I continue to believe that Foucault is not best thought of as a rhetorical theorist, his ideas have value as a way to understand power: how, through a combination of language and practices, large-scale changes to social norms occur.

I only wish people would stop using Foucault’s ideas (and those of other post-structuralist thinkers) to warrant new universal presumptions and essences. I strongly suspect Foucault would be mystified to learn his ideas were being appropriated in this way.

Recommended Parallel Reading

Foucault, History of Sexuality Vol. 1 (1976)

Foucault, Security, Territory, Population — Lectures at the Collége de France (1977–1978)

Barbara Biecker, “Michel Foucault and the Question of Rhetoric,” Rhetoric & Philosophy 25, no. 4 (1992): 351–364. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40237735

They took the German spelling of “critique” in honor of the Frankfurt School of critical theory from which many kritiks were generated.

Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, translated by Richard Howard (New York, Vintage, 1988), 35.

Ibid., 59.

Ibid., 246.

Ibid., 202.

As I understand him, Foucault would reject the possibility of universal truths altogether.

Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977, edited by Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 131.