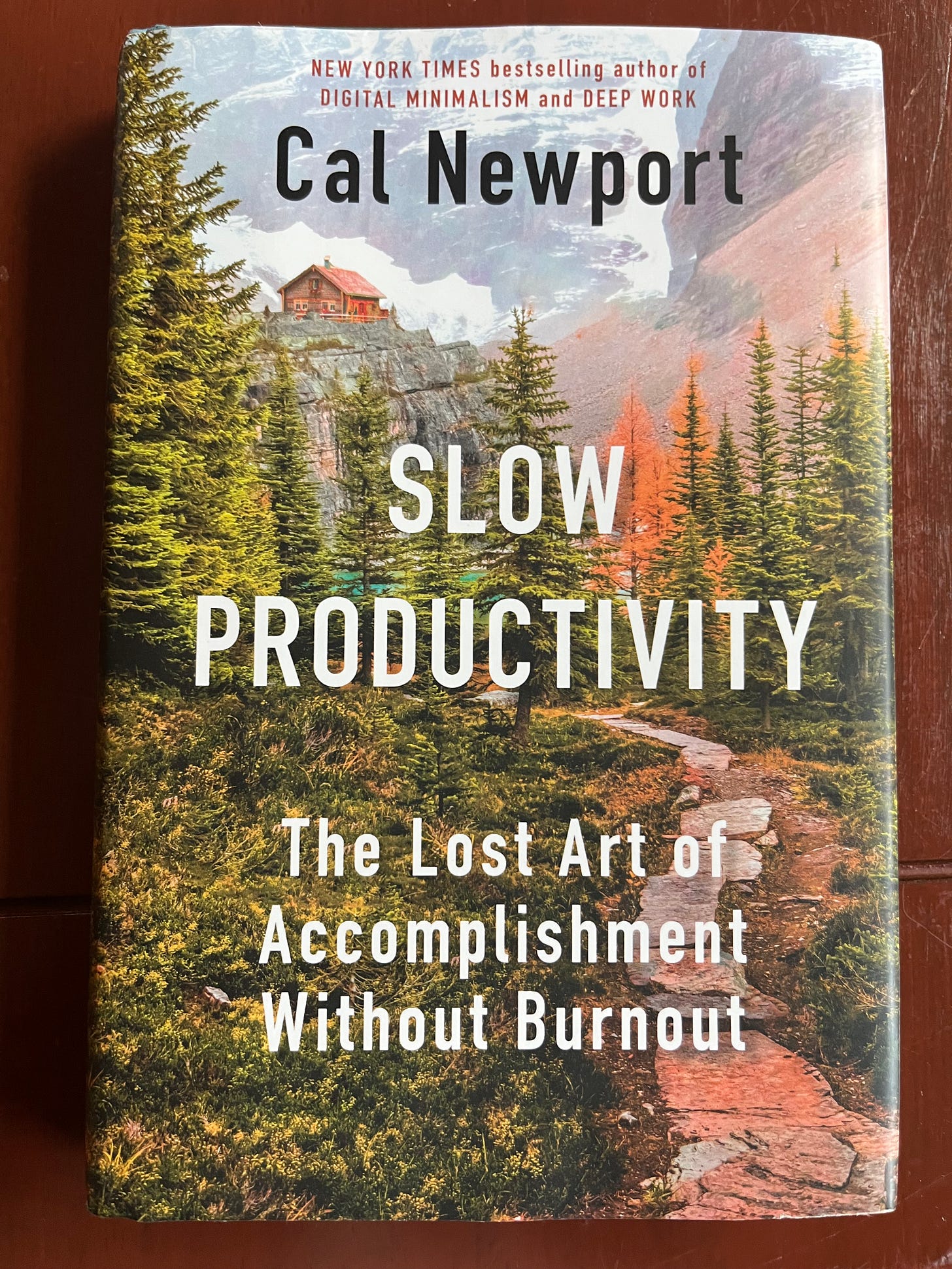

Can Knowledge Work be Saved from a Tyranny of Metrics?

A Review of Cal Newport's New Book, Slow Productivity (2024)

Is there a way for knowledge workers to reclaim their time? Georgetown computer scientist Cal Newport believes so, and offers three simple principles for doing so.

Newport is an academic as well as a prolific author for popular audiences. He is a contributing writer for the New Yorker and the author to three previous books about working in the technological age [Deep Work (2016), Digital Minimalism (2019), & A World Without Email (2021)]. He managed to complete graduate school, a post-doc, and earn tenure at Georgetown University while also writing outside his academic field, so perhaps he is onto something. (To give you a sense, his best-selling books appear on page 16 of 17 of his single spaced C.V.)

This short guide should be required reading for all white-collar managers. It takes shape in three parts. In the opening chapter, Newport analyzes the inherent difficulties of managing, and especially measuring outputs for, knowledge workers. Theories of productivity come from the industrial age, where one could easily measure the output of factory workers, and thereby evaluate their managers, in terms of the number of widgets produced.

However, when these practices are translated to knowledge work, things don’t go well. Instead of looking at things that should matter (i.e., quality and substance of deliverables), we measure little things that do not bear on anything worth caring about: emails answered, meetings attended, projects involved in, etc. My previous critiques of academic assessment also point to the pervasiveness of this: by assigning students tons of busy-work items, we teach them to pad their metrics and inculcate in them this distorted view of productivity.

This philosophy is what Newport calls pseudo-productivity, the idea of appearing busy by clogging your calendar with all sorts of obligations as a way to approximate worker output, as a factory manager might do. Despite being pervasive across government and the corporate world, this way of measuring works very poorly.

In the second part of the book, Newport outlines three principles of slow productivity. He defines this titular term as “a philosophy for organizing knowledge work efforts in a meaningful and sustainable manner.”1

The three principles are (1) Do fewer things, (2) Work at a natural pace, and (3) Obsess about quality. All three subsections offer case studies that feature prolific writers, scientists, and artists who practiced their craft in ways that exemplify the principle, followed by practical recommendations for the reader.

In what follows, I recount what I took to be the most meaningful exemplar of each principle and then articulate what lessons I would hope that knowledge workers and, especially, their bureaucratic overseers, might do in response. Although all the examples that resonated with me were of artists and writers, Newport includes examples from a range of fields, not just creative arts.

Principle #1: Do Fewer Things

The novelist Jane Austen’s personal story illustrates this principle well. In recounting how Austin came to be among the English literature’s most revered novelists, Newport dispels a widely-trafficked myth. Thanks to Austen’s nephew’s writings about his famous aunt, it was long believed that Jane wrote her novels by composing fragments on little slips of paper in between the ubiquitous social engagements required of women of her class.

It turns out, this story was embellished and mostly false. Although widely read and intellectually curious, Austen was neither happy nor a productive writer when she was busy. It was not until she moved to a small cottage in Chawton, freed from the obligations of high tea, that she finished her masterworks, Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility and wrote Emma and Mansfield Park.2

The lesson to be drawn from Austen’s example is precisely the opposite of what was long assumed. Austen did not show that by sheer will, one can manage a deluge of obligations and still produce masterpieces. This reality actually strengthens Virginia Woolf’s argument that writers need above all else A Room of One’s Own, a space of solitude and suitable time to write.3

Principle #2: Work at a Natural Pace

It is natural for writers to feel guilty whenever they are not writing. This premise applies similarly to most executives, managers, and academics (hence the scourge of mobile email). However, this guilt leads us into the trap of pseudo-productivity. Rather than give our important projects the time and attention necessary to make sure they are done well, we set unrealistic deadlines and force ourselves to produce outputs that are subpar. Oftentimes, we even put our important projects on hold to address urgent, but not important, tasks (email & meetings).

Lin Manuel Miranda, of Hamilton fame, is the case study for this principle that most resonated with me. Miranda was already highly accomplished at a young age, having written and staged the performance of his first musical, In the Heights, while still an undergraduate. However, the play went through numerous iterations and took years before it was ready for prime time. The first version, written in 2000, bore little resemblance with the one that would eventually open on Broadway, in 2008, and earn Miranda his first Tony Awards.

In what ranks among the best footnotes I’ve come across, Newport observed, “a few months after these triumphs [the success of In The Heights], Miranda would find himself lounging in a pool on a much-needed vacation, failing to find relaxation because his attention had been captured by a doorstop of a book . . . it was a biography of Alexander Hamilton.”4

What can we take from this section? (1) That creating value in the knowledge and creative sectors requires time and focus. It takes revision, a practice in which few of today’s students are willing to engage. (2) That working at a natural pace allows us to expand the horizons of our thinking. We need to do a lot of thinking and reading before we can expect to create something worthwhile.

Principle #3: Obsess Over Quality

Pseudo-productivity treats all outputs as the same. It does not regard quality, since quality is difficult to measure. If one took the first two of Newport’s principles to heart but did not embrace the third, all we would see is fewer outputs with no corresponding increase in value produced.

To enact the philosophy of slow productivity, we need to treat quality as the most important variable. To obsess over quality will require pushing back against incentive structures that favor the path of least resistance. Friction is necessary for and often generative of innovative ideas, great art, and valuable products.

The singer and songwriter Jewel’s early career epitomizes how knowledge workers can (and should) resist the demands of pseudo-productivity and its metrics. Jewel made it big, apparently, when a record company offered her a signing bonus of 1 million dollars. She turned it down.

She reasoned that if she accepted the advance, she would be forced to tailor her music to whatever executives believed would make the most money. She also thought that if she had an expensive contract with the label, they would be quicker to cut her if her first album wasn’t a hit. These beliefs were prescient and ultimately helped facilitate her success.

She made the music she wanted to make, how she wanted to make it, rather than capitulating to the demands of the industry. At first, her records did not sell especially well, but eventually quality won out. She was happier for having created the art she valued and held faith others would find value in it too. They did. Jewel has sold more than 30 million albums.

What can we do?

There is a lot of inertia behind pseudo-productivity. It will be hard to push against it, but we have little choice but to try.

Some of us may have the freedom to enact these principles on our own, and be happier, more productive, workers as a result. But for most of us, it is a massive collective action problem. If just a few workers here or there embrace slow productivity, they will be presumed lazy and will lose influence.

What we need to do is get thought leaders in business, government, etc., to read this book and start thinking seriously about how we might free knowledge workers from the tyranny of metrics.

Only once we’ve shaken loose the totalitarian handcuffs of Outlook, Microsoft Teams, and other “productivity” software might we be able to pursue real productivity in earnest. To start, I would propose two things. If you bristle because these will be understood immediately as non-starters in your organization, that is just proving the magnitude of the problem.

Opening Gambit #1: Limit meetings to designated times or days (i.e., no meetings before noon) such that at least 50% of your team’s work time will be meeting-free.

Opening Gambit #2: Set an organization-wide policy that no email needs to receive a response in less than 24 hours (so people can check email during designated times & remain focused on their important projects). The mere act of logging out of email applications will result in more actual productivity.

I wager that in adopting both, people will arrive prepared for and engage meaningfully in meetings, since they know this may be the only opportunity that day for them to get answers to their questions.

Cal Newport, Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment without Burnout (New York: Portfolio, 2024), 41.

Ibid., 51-2.

Woolf, too, recounts the myth of Austen’s business as support for her argument about women’s autonomy and creative productivity.

Ibid., 127.